|

GOLDSEA |

ASIAMS.NET |

ASIAN AMERICAN PERSONALITIES

THE 130 MOST INSPIRING ASIAN AMERICANS

OF ALL TIME

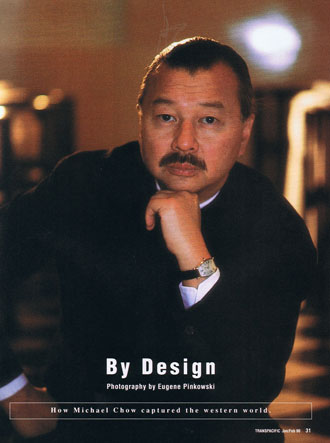

Michael Chow

by H Y Nahm

PAGE 1 OF 3

how might merit mention merely for his marriages to fashion maven Grace Coddington, tragic beauty Tina Chow and fashion designer Eva Chun -- and for fathering the lovely China Chow. But that's all incidental to a life as one of the 20th century's great asthetes and trendsetters. His four decades as actor, artist, restaurateur (Mr Chow's) and designer are all the more meaningful because they reveal his passion for restoring chic, chichi and chère to things Chinese.

how might merit mention merely for his marriages to fashion maven Grace Coddington, tragic beauty Tina Chow and fashion designer Eva Chun -- and for fathering the lovely China Chow. But that's all incidental to a life as one of the 20th century's great asthetes and trendsetters. His four decades as actor, artist, restaurateur (Mr Chow's) and designer are all the more meaningful because they reveal his passion for restoring chic, chichi and chère to things Chinese.

Michael Chow was born Chow Ying-Hua in February 1939 in Shanghai into a fashionable and respected family. He was the fifth of six children. His father, Chow Hsin Fang, who wrote over 300 plays, was China's grand master of Peking opera. He also recorded music, made films and was a voracious reader. Chow remembers his father as having led a simple, almost childlike life, being somewhat absent-minded and without interest in money. In fact, he was known to have received an allowance from his wife with which he bought a book every day. His favorite was Don Quixote. According to an autobiography by Tsai Chin, Michael's third eldest sister, the senior Chow was a taciturn and altruistic man. He was given the stage name Ch'i Lin-Tong because he was considered a prodigy at seven. During the Cultural Revolution he was jailed. After going blind he was placed under house arrest in his own study. He died in 1975 at the age of 80.

Michael's mother Lilin was born to a Chinese tea merchant and a Eurasian wife whose father was an Englishman named Ross. Lilin's father died when she was five. Lilin fell in love with the handsome and popular actor Chow Hsin-Fang, and the two eloped in 1928 when she was 23. The only problem was that Chow was already married with three children. His marriage to Lilin couldn't even become formalized until afer the birth of Susan and Cecilia, Michael's eldest sisters.

Lilin was known to have been a "talkative and materialistic" woman who maintained the family's finances. She died in 1968 at the age of 63 from beatings suffered during the Cultural Revolution, possibly in part because she was Catholic and spoke fluent English.

The last time Michael Chow saw his mother was in 1961 when she visited Tsai Chin and Michael in England. Her death seems to have left a mark on Chow. He finds himself crying alone from time to time for no apparent reason. Chow attributes this to the fact that for him there had been no proper period of mourning since he only learned of her death much later. He felt no strong emotions when he and the rest of his family returned to China in 1985 for a celebration of his father's 90th birthday.

Asthma made Michael a sickly child. He recalls the constant efforts of servants to feed him. His childhood memories include watching his father on stage and collecting stamps, exclusively Russian ones, and playing ball like other children. His mother gave him the English name Michael (he dislikes being called Mike) when he was still a baby. Even at that age he recalls being "concentrated and targeted."

In those days it was the practice of well established families to send their children abroad for education. The U.S., England and Japan were the favorite destinations. Chow wanted to go to the U.S. but for some reason he doesn't recall, he was sent to London with Tsai Chin. While Tsai Chin and his mother waited for the papers in Hong Kong, young Chow spent his last month in Shanghai with his father.

The elder Chow took his son everywhere. Chow visited his father backstage and watched him perform moments later. This month with his father seems to have planted in Chow a strong desire for perfection and perhaps too Chow's admitted fascination with glamour. Against his father's wishes Chow decided that he too would become a Peking opera actor.

After spending a month in Hong Kong with Lilin, Tsai Chin and Michael boarded a steamer for London. Michael was 13. Not being much of a letter writer, that was the last time he communicated with his father.

During his first few months in London Michael attended a girl's boarding school with Tsai Chin until his papers were in order. He went to art school for a year, then studied architecture for two and a half. To this lack of a formalized education Chow attributes his success. Too much education, he believes, prevents people from taking chances.

Revising his earlier ambition, Chow decided to become an artist. He specialized in abstract art and went through various color "periods". It was a difficult beginning. Once he starved for three days. When he began eating again he had to see a doctor for a severe case of constipation. He supported himself through part-time jobs working in farms, washing dishes, waiting in Chinese restaurants and playing occasional bit parts on stage and in films. The longest steady work he had was a part in The World of Suzie Wong (in which Tsai Chin had the title role) that ran for two years. His first real acting job was in 1957 in Violent Playground in which he played a Chinese laundry delivery boy. Being hungry he felt no regret playing that kind of role.

Chow recalls his art career as having been "very political". "An artist needs a country and a people to back him up and I didn't have those." In those days racism was rampant in London. There wasn't even a Chinese embassy. The few Chinese around Liverpool were mostly old Cantonese merchant seamen.

In 1959 Chow wore his hair long and Londoners thought he was crazy. He began affecting his trademark mustache in the early sixties, possibly to hide a weak chin "or something", he says. In the mid 60s he switched to a clean cut look which drew stares when he visited Hong Kong. Chow sees this as instances of being ahead of his time. People laughed at him over his concept for a Mr Chow restaurant. A few years later, everyone was copying him. "I'm always blamed for my actions and never given credit for them," Chow grouses. It's a source of constant frustration for him.

"It was lonely and sort of disciplined," Chow says by way of explaining why he gave up his art career in the late sixties. The racial and political aspects seem to have made it an embittering experience. In a 1977 interview with the international edition of Newsweek, Chow said half-seriously, "Being Chinese in the West is very limiting. It's either a Chinese restaurant or a laundry."

By his twenties Chow was already showing a knack for timeless design. He urged his girlfriend to open a hairdressing salon because she kept complaining about her employer. She agreed, and Chow designed it, mostly in white. He still calls it his "most brilliant design". Later, the salon was bought by Twiggy.

PAGE 2

1 |

2 |

3

Back To Main Page

|

|

|

|

Michael Chow was a featured profile in the January 1990 issue of Transpacific magazine.

|

|

“Once he starved for three days. When he began eating again he had to see a doctor for a severe case of constipation.”

|

CONTACT US

|

ADVERTISING INFO

© 1996-2013 Asian Media Group Inc

No part of the contents of this site may be reproduced without prior written permission.

|